How many of us current or former teachers would love the opportunity for a redo on those first one, two, or even three years?

Those unlucky students had us at the early phase of our learning curve and provided us with excellent “on the job training.” I often look back at those years with a sense of nostalgia in its truest form as “longing mixed with regret.”

The regret stems from all of the instructional mistakes I made with those classes and the hope that I didn’t too adversely impact the students’ futures. I left the classroom to become an instructional coach for teachers, principals, and district leaders—and unfortunately, I look back on those first few years of coaching with the same mixed feelings.

Flaws in Previous Coaching Models

My initial training as a coach and my first years coaching consisted of: first, analyzing a lesson for what I deemed to be the main strength and the main weakness; then, asking the teacher questions to lead them to those areas, making sure to pepper in the question “why” throughout the session. I know now that there are several inherent, structural flaws with this approach.

First, this type of “coaching” previously described (and still used with so many teachers across the nation) is not a true conversation or dialogue. Instead, it is the observer leading the observed to a specific outcome or conclusion. This approach does not honor the teacher’s input on what they self-identify as ways to strengthen their craft, which research shows is key to adult learning. It is simply one-way feedback disguised as two-way dialogue.

As a principal or teacher leader, when you sit down for a “coaching” session with your laptop or yellow legal pad and pen, ask yourself honestly if this is truly a coaching conversation or a feedback session. And then call it what it is, or more importantly, don’t call it what it’s not—coaching.

In fact, coaching is not scripted, but is embedded in a conversation. Coaches should not fear the impromptu coaching session; rather, when teachers do not even realize a conversation was actually coaching because it was truly a dialogue between professionals—fluid, natural, action oriented, and collegial—then you have truly become a coach.

Secondly, many coaching protocols were created in the late 1990s when instructional frameworks were focused almost exclusively on the actions of teachers. Today, our focus is on the learners. Coaching teachers or principals in a vacuum (i.e. without a framework to ground the conversation), can be very tricky for even the most experienced coaches and invites the common pitfall of basing the coaching conversation on opinion.

Specifically, a learner-centered framework is critical as the backbone of coaching sessions to focus the conversation on student action, skill, and learning. While many states and districts are shifting the focus of teaching and learning frameworks from teacher actions and behaviors to student actions and behaviors, too often the coaching conversations are not shifting in tandem and use the same methods for coaching regardless of the individual, context, or scenario.

Additionally, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to coaching, and the same approach for every educator in every situation will not help grow teachers—just like the same approach for every student will not help them learn.

Additionally, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to coaching, and the same approach for every educator in every situation will not help grow teachers—just like the same approach for every student will not help them learn.

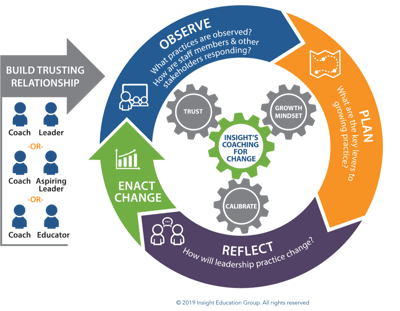

The approach and process for coaching is highly dependent on the situation, and effective coaches are familiar with multiple techniques, when to use each, and how to blend the approaches. At Insight, we codified a dozen coaching protocols in our Coaching for Change Playbook.

Lastly, I have come to see that “why” questions should be used sparingly as opposed to as the default question. In Chris Voss’s insightful work capturing his time as the FBI’s lead hostage negotiator in Never Split the Difference, he illustrates how “why” questions (and their overuse) may inhibit active problem solving by focusing exclusively on looking backward rather than looking forward towards solutions.

Side note: Any parent, aunt, uncle, or primary school teacher realizes that the question “why” used with unbridled repetition is just plain annoying, especially at 3:25 p.m. after a full day of teaching. As Voss (and I) recommend, coaches should rely much more heavily on the question “how” in order to shift the conversation into a mutual problem-solving session, which is where authentic coaching lies.

Five Practices for More Effective Coaching

In the spirit of transparency, openness, and dialogue, I have made all of the mistakes articulated above (more than once), but I have also learned from each, evolved, and continued to grow as a coach. So, how can you overcome these challenges to effective coaching?

Here are five “Do Nows” based on my experience (and mistakes) coaching leaders in the US and abroad.

- Put away the yellow legal pad and pen (or the laptop).

Be vulnerable as a learner and coach, and just talk and learn about instruction with teachers. - Ask sincere questions.

Coaches should not attempt to be attorneys who only ask questions to which they already know the answer; this coaching is disingenuous, and the teacher will only grow relative to YOUR instructional knowledge. - Coaching is community work.

The administrative team alone should not shoulder the burden of coaching; rather, they should model for all teachers how to engage in meaningful dialogue with one another. - Find or create a learner-centered framework for your school or district.

Many leaders focus instructional coaching on the state-level teacher evaluation instrument. However, many of these frameworks are very teacher-centric and will impede the depth of a coaching conversation about student learning. There are great resources out there, so create your own framework centered around learner skills and coach with a focus on the needs of the learner. - Read, Read, Read.

There are so many great resources for principals and teacher leaders in 21st century instruction, coaching, and leadership. With the number of directions principals and teacher leaders are pulled, if you want to get serious about your own learning, you need to prioritize it and put it on the calendar.

While I can’t go back in time and re-teach these early students or re-coach those early teachers, I can offer my lessons learned to help others navigate (and hopefully avoid) similar pitfalls. And I can continue to reflect, learn, and grow—because isn’t that what coaching is all about?

Want ideas for more good practices in coaching? Check out Insight's library of blog posts on instructional coaching.